There are three separate compartments in your engine:

-

The combustion chambers, one for each piston

-

The water jackets for cooling the engine

-

And the crankcase, the largest of all three compartments

While these are technically sealed from each other, the seals aren’t perfect, especially between the combustion and crankcase sections. As the pistons move inside the cylinders, gasses and vapors get past the sealing rings on the pistons. This is called “blow-by,” and it’s the reason you need a functioning positive crankcase ventilation (PCV) valve.

This blow-by is normal and happens in all engines from the first start. It happens at the first start when the piston rings have not yet seated—usually until the engine has 500-1,000 miles. In a perfect world, the crankcase should be at atmospheric pressure, but blow-by and thermal expansion make that impossible. If left alone, the pressure inside the crankcase builds quickly, which causes oil to push past the gaskets and seals.

Blow-by is considered a byproduct of combustion. It consists of vaporized oil and fuel, unburned excess fuel, and other nastiness. This all eventually condenses into liquid and mixes into the oil, becoming acid in the process. That’s what damages the bearings and produces engine sludge.

How a PCV Valve Works

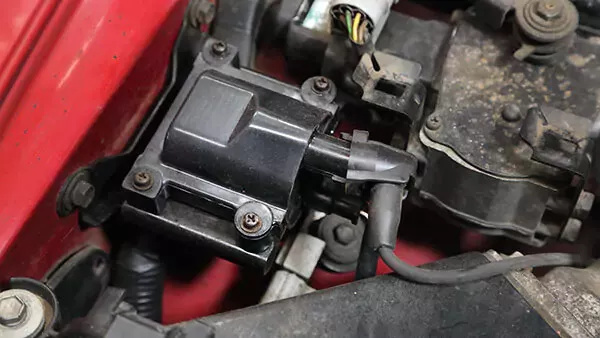

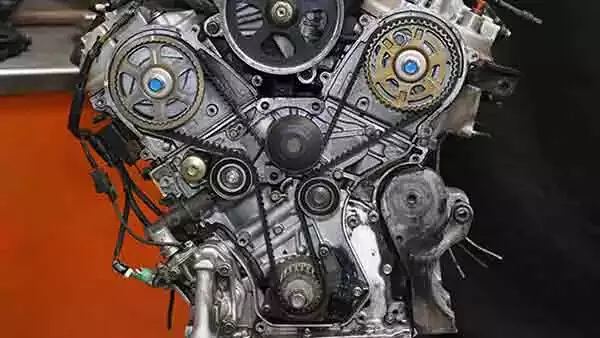

This 2014 GM LT1 V-8 places the PCV valve under the intake manifold. The port on the intake is directly above it.

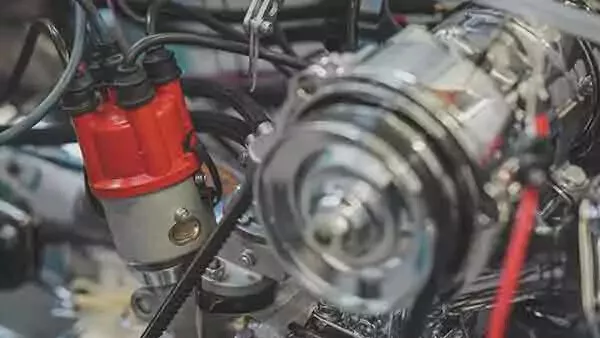

The positive crankcase ventilation (PCV) system was developed in the 1950s. It was the first emissions system created for cars. PCV use became mandatory in 1967. The early systems were simple—a valve connected to the vacuum system of the carburetor in one valve cover (or side of a single cover), and a filtered vent on the other.

The vent allows fresh air to enter the engine. The PCV valve draws out the dirty air, which is then recycled into the engine to burn it up. This device is credited for substantial reductions in smog in many large cities.

These days, every engine in every car has a PCV system. Some remain basic, but most are more complex. Most modern engines have a single PCV valve mounted in a valve cover or under the intake manifold, which is connected to the air inlet after the MAF sensor. You do not want oil vapor hitting the MAF sensor. You also do not want unmetered air entering the engine, so the fresh air inlets are plumbed to the air intake tube before the MAF.

The valve is simple. It’s a small, spring-loaded screened port that filters out oil mist and particles, so only gasses can enter. Under idle and light throttle, the valve stays mostly closed because the engine’s vacuum is high enough to close it. At higher rpm, the vacuum lowers, and the valve opens fully. This allows combustion gasses to be drawn into the engine and burned, reducing emissions. In the event of a backfire, the valve closes to prevent pressure being sent into the crankcase.

When the valve fails, the pressure in the crankcase builds. You get acidic oil, sludge formation, and oil leaks from the seals.

Many of the newest engine designs use the PCV system to help seal the piston rings. GM Gen V LT-series engines use rings that are too thin to seal the pistons on their own. Negative pressure (vacuum) in the crankcase pulls the rings to the cylinder walls, enabling them to complete the seal.

How to Tell If Your PCV Valve Is Bad

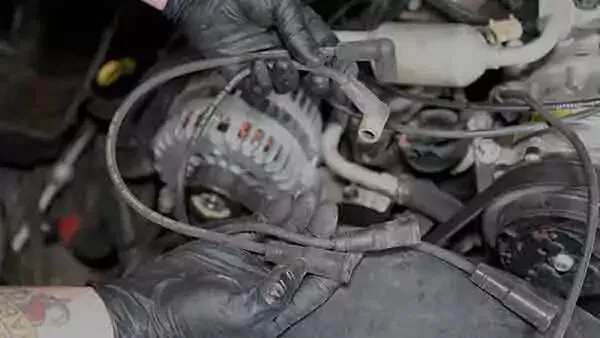

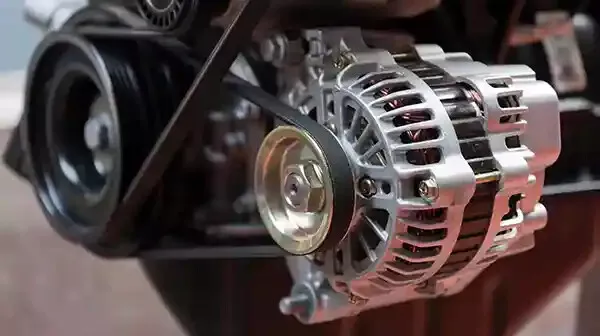

The valve is a vacuum fitting with a spring-loaded ball inside. This simple device plays a big role in emissions and engine performance.

The valve is a simple vacuum-operated unit. Shaking it should produce a tinny rattle like shaking a whistle. If it doesn’t rattle or if it makes a clunk or thudding sounds, it is bad.

You can test the valve with the engine running by removing the valve from the valve cover (that’s where it’s located if it’s in an older engine) and putting a finger over the port. At idle, you should feel a slight vacuum. If you blow through the valve at the top (where it connects to the intake), no air should pass through.

Other signs of a bad PCV are increased oil consumption, whistling from the engine, and excessive pressure or suction at the oil cap with the engine running.

If the PCV valve goes bad, your vehicle may set a code and light the check engine light (CEL). These PCV problem codes are commonly related to lean fuel or misfires:

P0106

: Manifold Absolute Pressure (MAP) Sensor Performance

P0171

: System Too Lean (Bank 1)

P0174

: System Too Lean (Bank 2)

P2195

: O2 Sensor Signal Biased/Stuck Lean – Bank 1, Sensor 1

P2279

: Intake Air System Leak

P0300

: Random Cylinder Misfire Detected

These codes might be completely unrelated to the PCV. We recommend testing the valve as described above.

Can You Clean a PCV Valve?

PCV valves can be cleaned, but they are affordable. Replacing them is better in the long run.

Yes. Everything that gets in a PCV valve is oil based, so a carburetor cleaner works well to clean a fouled PCV valve. Soak the valve in carburetor cleaner for about 10 minutes, rinse off with water (tap water is fine), and reinstall. There is no standard replacement schedule for a PCV valve. Cleaning the PCV every so often helps it last longer. However, PCV valves are affordable, so replacing them is easier and better in the long run.

What does a new PCV valve cost?

The average cost of a new PCV valve ranges from $10 to $40. However, some engines have molded plastic hoses that connect the valve to the engine. If this breaks, it could cost $25 to $65 to replace the hose. On most engines, it takes less than 10 minutes to change the PCV valve. If your vehicle buries the PCV valve under tons of unrelated parts, it could add more time to the project.

Share your feedback

This article is meant to provide general guidance only. Automotive maintenance, repair, upgrade, and installation may depend on vehicle-specifics such as make and model. Always consult your owner's manual, repair guide for specific information for your particular vehicle and consider a licensed auto-care professional's help as well, particularly for advance repairs.